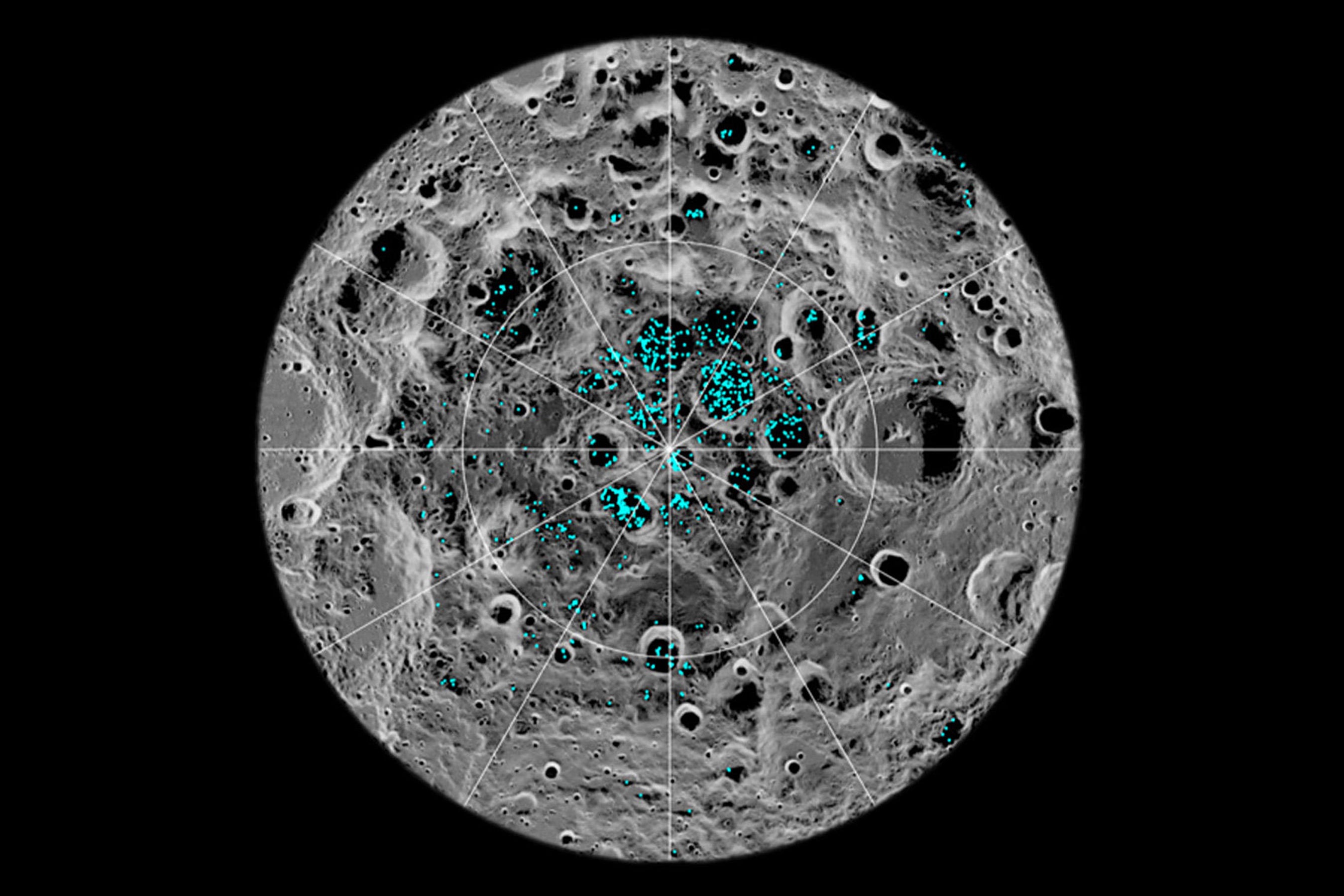

We are trying to learn more about the predicted ice conditions in the Moon’s Permanent Shadow Regions (PSR). Several countries are eyeing the lunar south pole, and researchers plan where and how to explore the bottom of the sun-blocking terrain.

But there are proposals in some circles to suspend PSR workup on the moon. While they may be chock-full of extractable ice, these functions may need to be protected because of the science they may offer.

Since the PSR acts as a “palespace tape recorder”, it must be stored on the lunar pole. However, much more modeling work is needed to measure the effects of warm spacecraft, rovers and even spacesuits on these environments. Doing so will ensure that no unintentional defacement occurs before such a basic record has a chance to be studied.

Nonetheless, a number of new studies have identified areas of particular interest within the proposed landing site for Artemis 3 that may harbor water ice that could be exploited by future crews on the moon. But how realistic is it to expect to find enough ice on the Moon to support human habitation? And what are the challenges involved in mining and using resources on the Moon? ?

Related: NASA’s Artemis Program: Everything You Need to Know

cold trap

NASA’s Artemis 3 mission (American “Moon Reboot” by Human Explorers) aims to land a human crew near the South Pole of the Moon. The moon’s south pole lies on the rim of Shackleton Crater, a 13-mile (21-kilometer)-diameter feature carved out by an asteroid impact billions of years ago. Shackleton’s interior is permanently shrouded in shadow.

Artemis 3’s exact landing site is not yet known, but a preferred touchdown spot is near the PSR. There are also attractive places in the lunar landscape where sunlight is available for long periods of time and direct communication with Earth is possible.

The South Pole of the Moon is surrounded by highly illuminated crests, which could provide access to solar power in areas that also include the PSR. This area is a “cold trap” believed to contain volatile elements that can be turned into useful substances, capable of shielding from radiation and even possible. rocket fuel.

unique locale

Considered a unique place in Antarctica is the “connecting ridge” between Shackleton and Henson craters. This may be an ideal target for future sampling tasks that can detect large numbers of features at short distances.

A detailed survey of the connecting ridges will provide a geological resource for gathering the potential resources needed to sustain human habitat should this site become the subject of a permanent lunar outpost in the future. will provide background.

That’s the view of Sarah Boasman, lead author of a recent study based at the European Space Agency’s ESTEC in the Netherlands that explored geological targets near the Moon’s south pole.

“Investigations of the Lunar Antarctic region should continue to assess the accessibility of target features such as isolated rocks, outcroppings, rocky craters and PSR in preparation for future missions to this region. Yes,” explains Boisman and colleagues. “Such surveys will provide an important background for future efforts to explore the lunar south pole.”

big and flat

Some of the connecting ridges are just over a kilometer wide, said David Kling, chief scientist at the Institute for Lunar and Planetary Studies at the University of Houston, Texas. There’s an area on the ridge that’s wide and flat enough to meet the requirements of NASA’s Artemis manned landing system, a lunar machine that explores the moon’s surface, he said.

“Ridges are typically hundreds of meters wide and are dotted with small impact craters. Some of those crater walls are steep and should be avoided. , which could make the crater floor appear deeper than it actually is,” Kling told Space.com.

Craters may seem like a nuisance, Kling added, but craters are important probes on the moon’s surface. “The drilling process that created the crater carried material from depths where astronauts could access it to the surface,” he said.

any shape and size

Pascal Lee is a planetary scientist at the SETI and Mars Institute, based at the NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California.

Lee said it’s important to realize that PSRs come in all shapes and sizes on the moon, ranging from large areas that can actually be called “regions” to much smaller patches around rock bottoms, regolith grains. Every corner in between, he says. . “Instead, I think we should use the more general expression ‘permanent shadow area’ or ‘PSA’.”

It’s also important to recognize that there is no one-to-one match between the PSR and lunar polar water ice, Lee added.

“Some of the PSR appear to have very little hydrogen,” Lee said. “On the other hand, there are occasional sunlit regions, and surprisingly, traces of hydrogen are still visible within the upper meters of the regolith.” dust, crushed stones, and other substances.

international company

Last November, an interagency working group within the National Science and Technology Council at the White House produced the Lunar Satellite Technology Strategy. The strategy explains on its page that new technologies are needed to explore the lunar poles, which “may contain large amounts of volatile compounds that are of particular importance for resource exploitation.”

The strategy report also proposes an International Lunar Year (ILY).

“Science is an international enterprise, and scientists have long demonstrated the ability to work across boundaries for the common good,” the report explains. “The U.S.-led effort to establish an International Lunar Year (ILY) builds on the historical examples of past International Polar Years (IPY), International Geophysical Years (IGY), and International Space Years (ISY). I can.

The report also states that the ILY will “enhance transparency, build trust and cooperation among lunar tourism operators, and take responsibility for its various activities for the benefit and benefit of all nations, including developing nations.” We can demonstrate how we can have it and do it.”

artemis base camp

NASA’s primary goal is to develop sustainable lunar exploration, building on the legacy of the Apollo program’s 1969-1972 human journeys to the moon.

However, an evaluation by the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (LEAG) found the details of Artemis Base Camp to be too sketchy.

LEAG analyzes scientific, technical, commercial, and operational issues to support lunar exploration objectives and their impact on lunar architectural planning and prioritization of lunar surface activities. was established in 2004 to help NASA provide

“Artemis will not be truly sustainable unless it incorporates robust surface infrastructure and development strategies into a single location on the Moon to facilitate and enable commercial and exploration activities. progress is encouraging, but the details of ‘sustainability’ are unclear. The stage of the Artemis campaign is ambiguous to the wider community,” the 2022 LEAG document states.

Therefore, LEAG has stated to NASA that it will enable the construction of Artemis Base Camp and the establishment of large-scale resource production by 2030, thereby ensuring the permanent presence of humans on the Moon and the growth of a thriving lunar economy. I asked for clarification of the plan to support.

property rights

Moon mining will likely be one of the first big challenges for space ownership, says Erica Nesbold, author of new book Extraterrestrial: Ethical Questions and Predicaments for Living in Outer Space (MIT Press, 2023). says Mr.

“Outer space itself may be limitless, but the precious space resources within our reach are not, and our international treaties and domestic legal systems have limited resources such as ice. Whether it will lead us to cooperation, competition or conflict remains to be seen: the moon,” Nesvold told Space.com.

“First come, first serve” is certainly an attractive model for companies with the resources to get there first, and for governments looking to encourage and stimulate their own private space mining industries, Nesbold said. added Mr.

“Ethically, however, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty states that activities in outer space should be ‘conducted for the benefit and benefit of all nations, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development.’ It contradicts established ideals,” Nesvold points out.

So how do we curb potential conflicts?

Nesvold said, “Just as we tackle such a big and thorny problem here on Earth, we should use deliberate effort and foresight to help all countries, including countries that cannot yet mine the moon. “We have to work in consultation with stakeholders,” he said. A serious consideration of the impact of the decision on future generations and on the lunar environment itself requires “significant effort by space lawyers and diplomats.”

water tower

Meanwhile, NASA’s Pascal Lee raises a flag of caution against the PSR.

“I think it’s too early to talk about water as a monthly resource,” says Lee. “Something is a ‘resource’ only if it is economically cheaper and less risky to extract it locally than to import it from elsewhere.”

Lee points out that SpaceX Starship has the ability to land more than 100 tons of clean, purified and ready-to-use water anywhere on the Moon in a single flight.

“In effect, you put a water tower on the moon, put a faucet on the bottom of it, and put it where you want it. says Mr.

So the real question is when will 100 tons of clean, treated water extracted at the lunar poles and placed where we want it cost less than tens of millions of dollars? ?

“I am optimistic about the moon’s future,” Lee concluded. “But honestly, it will still take a very long time, if at all. The largest source of water available on the Moon is Earth.”

Copyright 2023 Space.com, a company of the future. all rights reserved. You may not publish, broadcast, rewrite or redistribute this material.