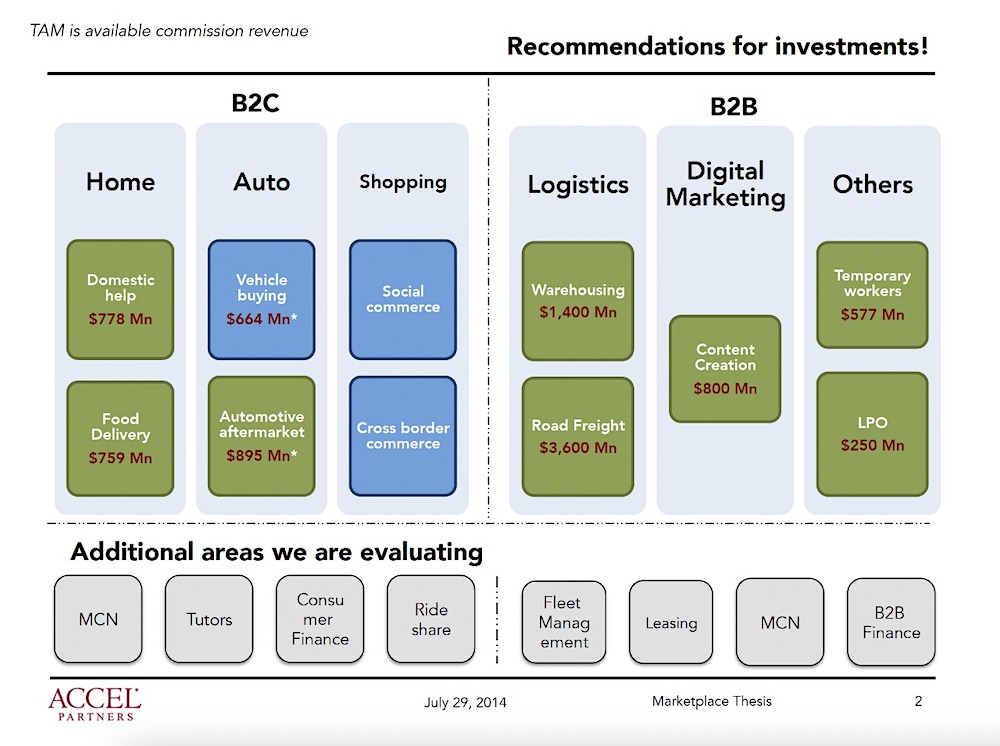

2014, Playank Swaroop pitched the future market in India to the well-known venture company Accel, where he worked as an associate.

At the time, Flipkart and Snapdeal were the only two e-commerce startups of any size in India. Swaroop argued that as more Indians come online, there will be opportunities in many other market areas such as food delivery, auto aftermarket, warehousing, road transportation and social commerce.

Now it turns out that the company’s partner, Swaroop, was right. Urban Company, which operates in the domestic assistance sector, is valued at over $2 billion. Zomato and Swiggy deliver food to millions of customers every month. Spinny and Cars24 sell hundreds of thousands of cars each quarter. Social commerce startup DealShare is valued above his $2 billion valuation, while Meesho’s is just below his $5 billion valuation.

Hundreds of millions of Indians have gone online over the past decade, with over 100 million making online transactions and purchases each month. India, which has doubled its pool of unicorns to more than 100 in the last two years, has received more than $75 billion from tech giants Google, Meta, Amazon and venture funds Sequoia, Tiger Global, SoftBank, Alpha Wave, Lightspeed and Accel. are attracting investment. For the past 5 years.

2014 Swaroop presentation (Image credit: Accel)

But after one of the toughest years for the local startup ecosystem, it faces another problem that has long been dismissed as innocuous.

About six Indian consumer tech startups have gone public in the past year and a half, all of which have performed poorly on local stock exchanges. Paytm is down 60% this year, Zomato is down 58%, Nykaa is down 56%, Policy Bazaar is down 52% and Delhi is down 38%.

This is despite Indian stocks outperforming the S&P 500 and China’s CSI 300 this year. India’s Sensex – the local equity benchmark – continues to rise 3.4% this year, compared to a 19.75% decline in the S&P 500 and a 21% decline in China’s CSI 300.

A number of Indian startups, including MobiKwik and Snapdeal, have postponed their plans to go public this year as the market changed direction. OYO, which was set to go public in January, is unlikely to go ahead with its plans, according to two people familiar with the matter.

Walmart-majority-owned Flipkart, valued at $37.6 billion, isn’t expected to go public until at least 2024, according to people familiar with the matter. Byju’s, India’s most valuable start-up, has no plans to go public in 2023, instead pursuing plans to list one of its subsidiaries, Aakash, next year, TechCrunch previously reported.

Companies looking to move forward with their plans to go public will face another obstacle: Several global public funds, including Invesco, which has been keen to fund pre-IPO rounds, are set to drop this year. It is pulling out of the Indian market after being hit in China and other emerging markets.

LPs have long expressed concern about India’s failure to deliver an exit, and early attempts from the industry over the past two years appear to be unremarkable.

Venture funds in India have historically obtained most exits through mergers and acquisitions. But even these exits are becoming increasingly difficult to come by.

An analyst at one of India’s top venture funds said VCs backing early-stage SaaS startups with valuations under $25 million have a long-term chance of making a good exit. But as we’ve seen in several cases in recent months, the exit itself drives the startup’s valuation below his $25 million, making it difficult for SaaS investors to turn a profit.

Ⅱ

At a closed-door gathering of dozens of industry insiders at a five-star hotel in Bangalore on a recent evening, many investors exchanged notes on deals under evaluation. Partners complained that the quality of startups had declined despite a surge in pitch volume.

Two prominent venture funds, which run well-reputed accelerator and early-stage investment cohort programs, are struggling to find enough candidates for their next batch, said a person familiar with the matter.

I would argue that not only is the quality of emerging startups taking a hit, but so are investor appetites and mental models of what they think will work in the future.

Take ciphers, for example. The majority of Indian investors were too late to invest in the web3 space. (As pointed out to me by local exchanges CoinSwitch Kuber and CoinDCX, and until recently as prominent VCs on one of the world’s largest cryptocurrency VC funds, blockchain scaling company Polygon’s cap table until recently had India’s I rarely find names.)

A number of Indian firms that hired a number of cryptocurrency analysts and associates last year are pulling out of the web3 market and asking their employees to focus on other sectors, according to people familiar with the matter.

Fintech is another concern for investors. India’s central bank has made a series of drastic changes this year to how fintechs lend to borrowers. The Reserve Bank of India is also scrutinizing more and more who gets the license to operate a non-bank financial company in the country, in a move that has shocked investors.

Many venture investors are now increasingly chasing opportunities to back banks instead. Accel and Quona recently backed Shivalik Small Finance Bank. Many are considering investing in SBM Bank India, one of the banks actively partnering with fintech companies in the South Asian market, TechCrunch reported earlier this month.

One investor described the trend as a “hedge” against fintech exposure.

Investor enthusiasm for the edtech market also cooled after the reopening of schools led to the bankruptcy of giants such as Byju’s, Unacademy and Vedantu.

Indian startups raised $24.7 billion this year, up from $37 billion last year, according to market research firm Tracxn. Startups laid off as many as 20,000 employees this year due to lack of funding and market dynamics.

A dozen investors I spoke to said the funding shortfall would be cleared at least until the third quarter of next year, even though most of them are chasing India with record amounts of dry powder. I don’t think so.

As we enter the new year, some investors are reassessing their beliefs, with many believing that several major startup down rounds are on the horizon. But many star unicorn founders are reluctant to lower their valuations. Valued at $5.6 billion, PharmEasy was offered new capital this year at a valuation of less than $3 billion, according to two people familiar with the matter. (PharmEasy did not respond to a request for comment.)

“2022 is off to a strong start and for a while it seemed like India’s venture funding market would be under a different gravitational pull than the US and China, which have seen dramatic declines, but that is not the case. No. The Indian market ended up facing the same macro headwinds as the US and Chinese venture markets,” said Sajith Pai, an investor at Blume Ventures.

Growth-stage deals accounted for the majority of funding last year, and are down 40-50% this year, Pai said. “The decline was largely due to growth funds suspending investments as private market multiples were higher than listed companies, and weaker unit economics for growth stage companies.”