Mammals live only once, but their lifespans vary in length. While some shrews can limp from this mortal coil in as little as 14 months, a bowhead whale can swim for more than two centuries in the Arctic Ocean. And life isn’t just about size. For example, a 250-pound brown bear (with a maximum lifespan of 40 years) outlives, on average, a blunt bat (with a maximum lifespan of 41 years), a species small enough to fit in the palm of a human hand.

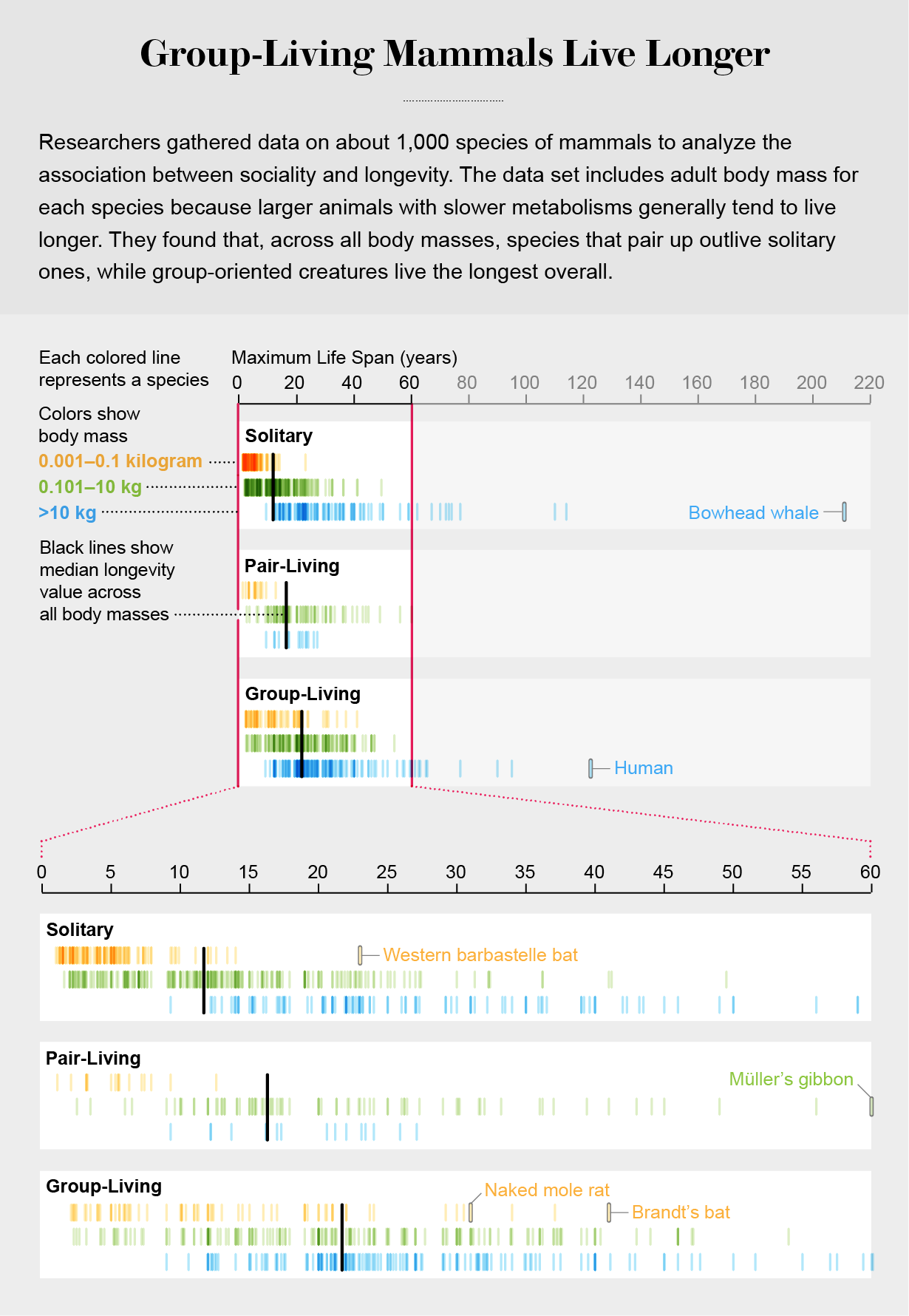

Instead, one of the most important factors affecting a mammal’s lifespan may be the company it sustains. The research team recently analyzed the lifespans and lifestyles of nearly 1,000 species of mammals, from aardvarks to zebras.In a study released Tuesday Nature CommunicationsThe research team found that mammals that live in groups, such as ring-tailed lemurs and elephants, generally live longer than solitary species such as tigers and chipmunks.

The project began when evolutionary biologist Xuming Zhou and his colleagues at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, were investigating aging in very long-lived mammals. The longevity of a particular species, the naked mole rat, jumped out. These bucktoothed, wrinkled rodents can live up to 31 years, longer than some much larger mammals such as wolves and bighorn sheep.

These hairless rodents exhibit not only longevity, but also one of the most complex social structures known in mammals. In other words, a queen mobar rat and a caste of non-breeding workers live together in underground burrows. Some other social mammals, especially primates, also have long lifespans, and their relationships may extend to individual animals within a single species. Female chakma baboons were found to live longer than their less social counterparts.

To determine whether a link exists between sociability and longevity on a broader scale, Zhou and his team combed the scientific literature on maximum lifespans of 974 different mammalian species. They classified this fauna into groups based on her three mammalian lifestyles.

They found that being part of a pack was better than being a lone wolf when it came to living longer. They tended to live longer, but group-living species like elephants generally lived the longest. This trend was also true when the researchers examined similarly sized mammals. For example, a giant shrew weighs about the same as a giant beetle bat. A solitary shrew can only live for about two years, while a bat that lives in groups can fly for more than 30 years.

According to Zhou, there were some exceptions to this trend. “Sumatran orangutans are generally solitary, but can live up to 60 years. [while] Some group-living rodents, such as Bennett chinchilla rats and Norwegian rats, live only two to four years,” he says. The biggest outlier is the bowhead whale. These leviathans are often loners, but can live over 200 years, more than twice as long as he in more social species such as sperm and humpback whales.

However, most of the mammals investigated in the new study support that connection, and the researchers concluded that social organization and longevity likely evolved together in mammals.

According to Brenda Bradley, a bioanthropologist at George Washington University who studies primate population genetics but was not involved in the new study, examining such a wide range of mammalian diversity would be a “These variables are often difficult to disentangle, but the beauty of large-scale comparative analyzes such as this new study is that they begin to decompose them.” It’s possible,” she says.

These traits may be evolutionarily related for several reasons. Researchers speculate that mammals that live in groups tend to be less susceptible to predation and starvation than solitary mammals. In addition, social animals tend to live at a slower pace instead of rushing into reproductive age to produce offspring. Nurture, which benefits future survival. Together, these advantages may outweigh the disadvantages of living in large groups, such as competition for food and companionship. Bonds have the power to extend life,” says Zhou.

To identify specific genes that may contribute to the relationship between sociability and longevity, the researchers dissected about 300 brain samples from 94 mammal species. The brain was from a species with a maximum age of just over 3 years he (Chinese mole) to a species with a maximum age of 122 years he and older (human). After dissection, brain samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and analyzed in detail under a microscope.

The team identified 31 genetic traits associated with both social organization and longevity. Many of these features enhance immune responses or regulate hormones. Strong immunity is essential in large groups, as parasites and pathogens can spread rapidly between related individuals living in close quarters. Helps mammals with grooming, mating and even parenting.

Linking social genes to longevity was intriguing, according to Daniel Blumstein, a conservation biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles who has studied the lifespan of yellowberry marmots and was not involved in the study. “What was very cool was that it was not just an immunological gene, but a gene that seemed to explain sociability,” he says. According to Bloomstein, continuing to unravel the genetic mechanisms linking longevity and sociability will help researchers determine how these traits co-evolved in bats, whales, and all mammals in between. It is useful for