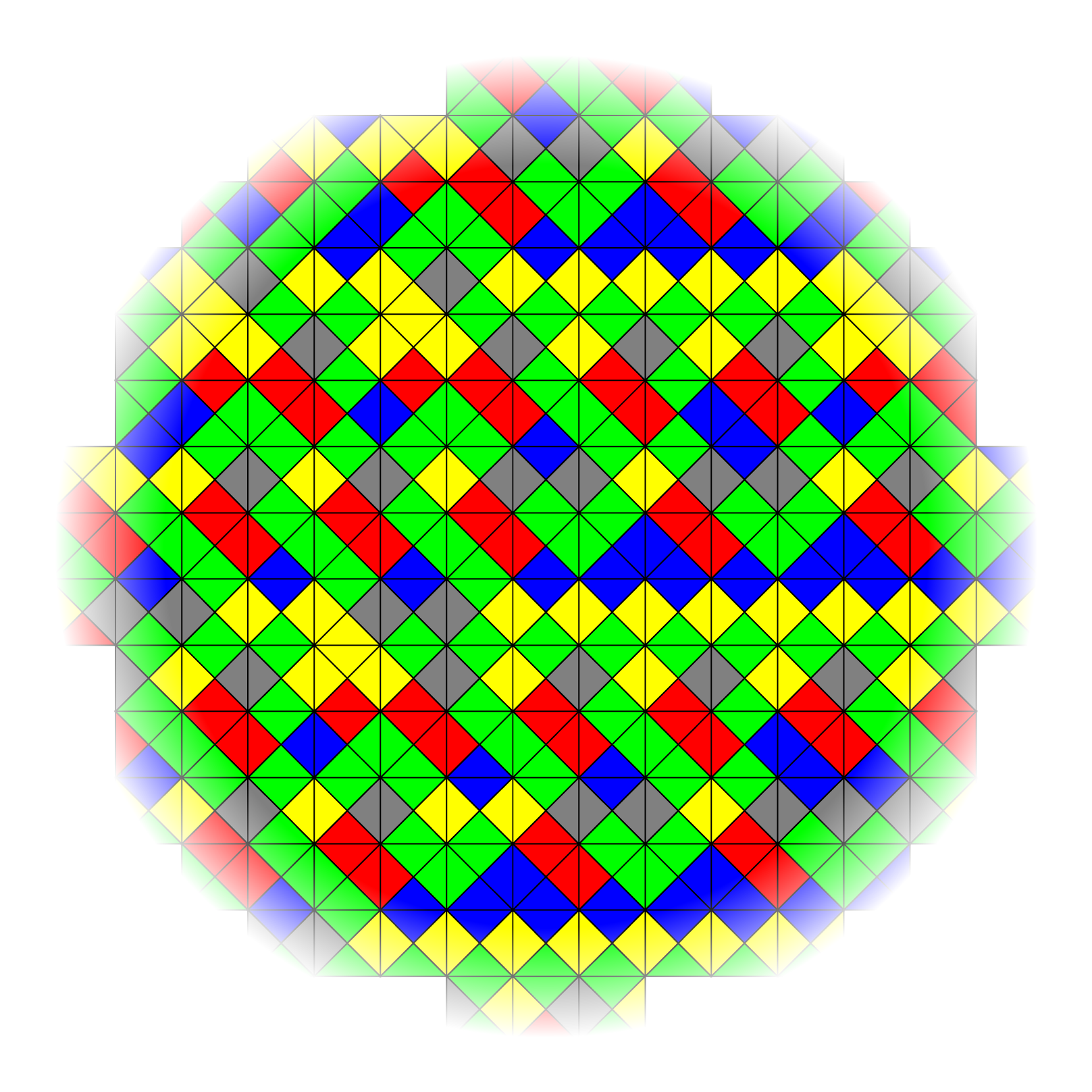

Creatively tiling bathroom floors isn’t just a stressful task for DIY home remodelers. He is also one of the hardest problems in mathematics. For centuries, experts have studied the special properties of tile shapes that allow them to cover floors, kitchen backsplashes, or infinitely large flat surfaces without leaving gaps. Mathematicians are interested in tile shapes that can cover an entire plane without creating repetitive designs. In these special cases, called aperiodic tilings, there is no pattern that can be copied and pasted to preserve the tiling. No matter how you chop up your mosaic, each section is unique.

Until now, aperiodic tiling always required at least two differently shaped tiles. Many mathematicians had already given up hope of finding a solution in his one tile, called the “Einstein” tile, which means “one stone” in German.

Then, last November, David Smith, a former printing systems engineer in Yorkshire, England, made a breakthrough. He discovered 13-sided craggy shapes that Einstein believed he could be tiles. When he told Craig Kaplan, a computer scientist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Kaplan immediately recognized the shape’s potential. Kaplan, along with software developer Joseph Samuel Myers and University of Arkansas mathematician Chime Goodman his Strauss proved that Smith’s idiosyncratic tiles actually pave a flat surface without gaps or repeats. Even better, they found that Smith found an infinite number of Einstein tiles, not just his one. The team recently reported their findings in a paper that has been posted to preprint his server arXiv.org and has not yet been peer-reviewed.

From beautiful patterns to unprovable questions

Anyone who has walked through the breathtaking mosaic corridors of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, knows the artistry of airplane tiling. But such beauty lurks unanswered questions. It is an unprovable question, as mathematician Robert Berger put it in his 1966.

Suppose we want to tile an infinite surface with an infinite number of square tiles. However, one rule must be followed. The edges of the tiles are colored and only edges with the same color can touch.

Start arranging pieces using infinite tiles. You find a strategy that seems to work, but at some point you hit a dead end. There are gaps that cannot be filled with available tiles, and the mismatched edges must be placed next to each other. game over.

But sure, having the right tiles with the right color combination would have gotten you out of the pickle. A mathematician looks at your game and asks, “Can you tell if you hit a dead end just by looking at the type of tiles of a given color at the beginning?” This saves a lot of time. ”

The answer Berger found is no. There will always be times when it is not possible to predict whether a surface can be covered without gaps. Cause: Unpredictable and non-repeating nature of aperiodic tiling. In his work, Berger discovered an incredibly large set of 20,426 differently colored tiles that could pave a flat surface without repeating color patterns. Even better, it’s physically impossible for that set of tiles to form a repeating pattern, no matter how they’re arranged.

This discovery raised another question that has puzzled mathematicians ever since: What is the minimum number of tile shapes that can together create an aperiodic tessellation?

how far can it go down?

In the decades that followed, mathematicians discovered sets of smaller and smaller tiles that could create aperiodic mosaics. First, Berger he found one with 104 different tiles. Then in 1968 computer scientist Donald Knuth discovered his 92 examples. A year later, mathematician Raphael Robinson discovered his variant with only six tiles, and in 1974 physicist Roger Penrose published his solution using only two tiles.

.png)

After that, progress stalled. Since then, many mathematicians have searched for a single tile solution, ‘Einstein’, but none have been successful. Penrose eventually turned his attention to other puzzles. But 64-year-old retiree David Smith wasn’t giving up. He loved playing with his PolyForm Puzzle Solver. PolyForm Puzzle Solver is software that allows users to design and assemble tiles. new york timesIf a shape looked promising, Smith cut out some paper puzzle pieces to experiment with. Then, in November 2022, I came across a famous tile called “Hat” because of its top hat shape.

_webp.jpeg)

When Kaplan received an email from Smith containing a “hat,” he was immediately intrigued. With the help of software, he laid out more and more hat-shaped tiles. It seemed to actually cover the plane without forming a repeat of the pattern.

But if he kept laying tiles, such repeating patterns could become apparent. Perhaps when the plane is a few light-years long, the extra parts just show up. Researchers had to prove mathematically that the tilings were aperiodic. Kaplan turned to Myers and his Goodman-Strauss, who had worked extensively with tiles in the past.

At first, I was struck by the simplicity of potential Einstein tiles, as the “hat” has a fairly simple 13-sided shape. If you had asked Goodman-Strauss what the previously elusive Einstein tile would look like, he said, “I would have painted something crazy, squiggly and nasty.” science newsAnd as mathematicians took a closer look at the shapes, they realized that you could play around with the length of the sides and still create seamless, aperiodic mosaics. This he did in one form, but opened the door to countless Einsteins in his tiles.

non-repeating pattern

Mathematicians needed hard evidence to support their claims. First, using methods that experts have trusted for decades, we showed that certain types of tiles can create aperiodic mosaics. But Myers went beyond these old methods and created a whole new way to prove it. This may also be useful for other tilings.

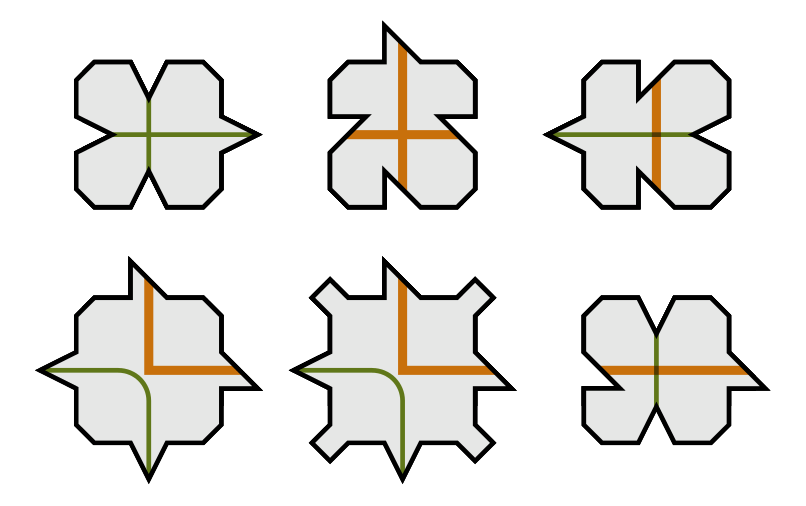

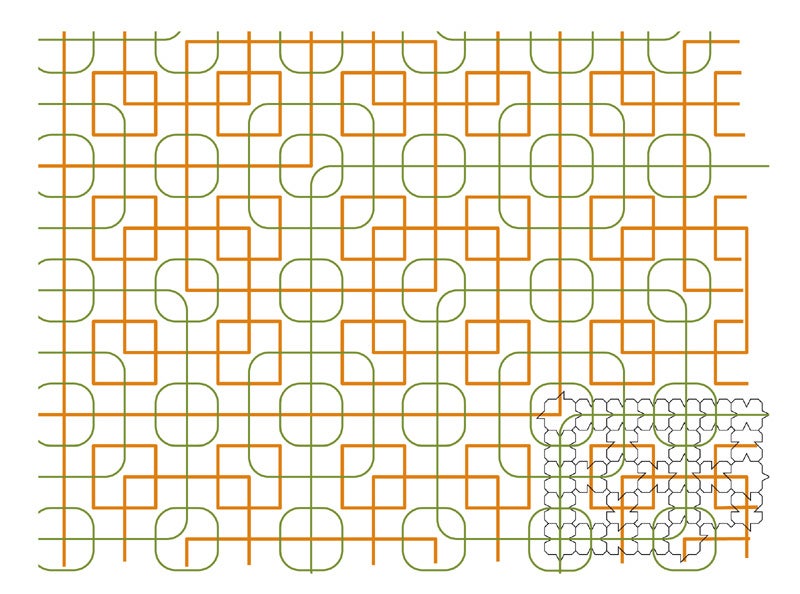

The proven method is best illustrated using Robinson’s 6 tile set from 1969. The orange and green lines drawn on Robinson’s tiles act like the colored edges in the previous infinite square example. The rules here are similarly simple: you can only place two Robinson tiles next to each other if the green and orange lines continue smoothly.

If you follow this rule, you will get a recognizable pattern of larger and larger orange squares. As you keep zooming out, the squares keep getting bigger and intersecting each other. This builds a hierarchical structure where each piece of the mosaic has its own location. Sections cannot be moved or swapped without breaking the rules or destroying the structure. This indicates that the tessellation must be aperiodic.

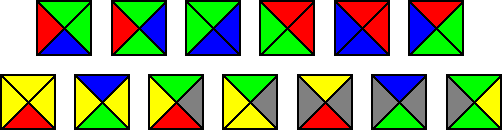

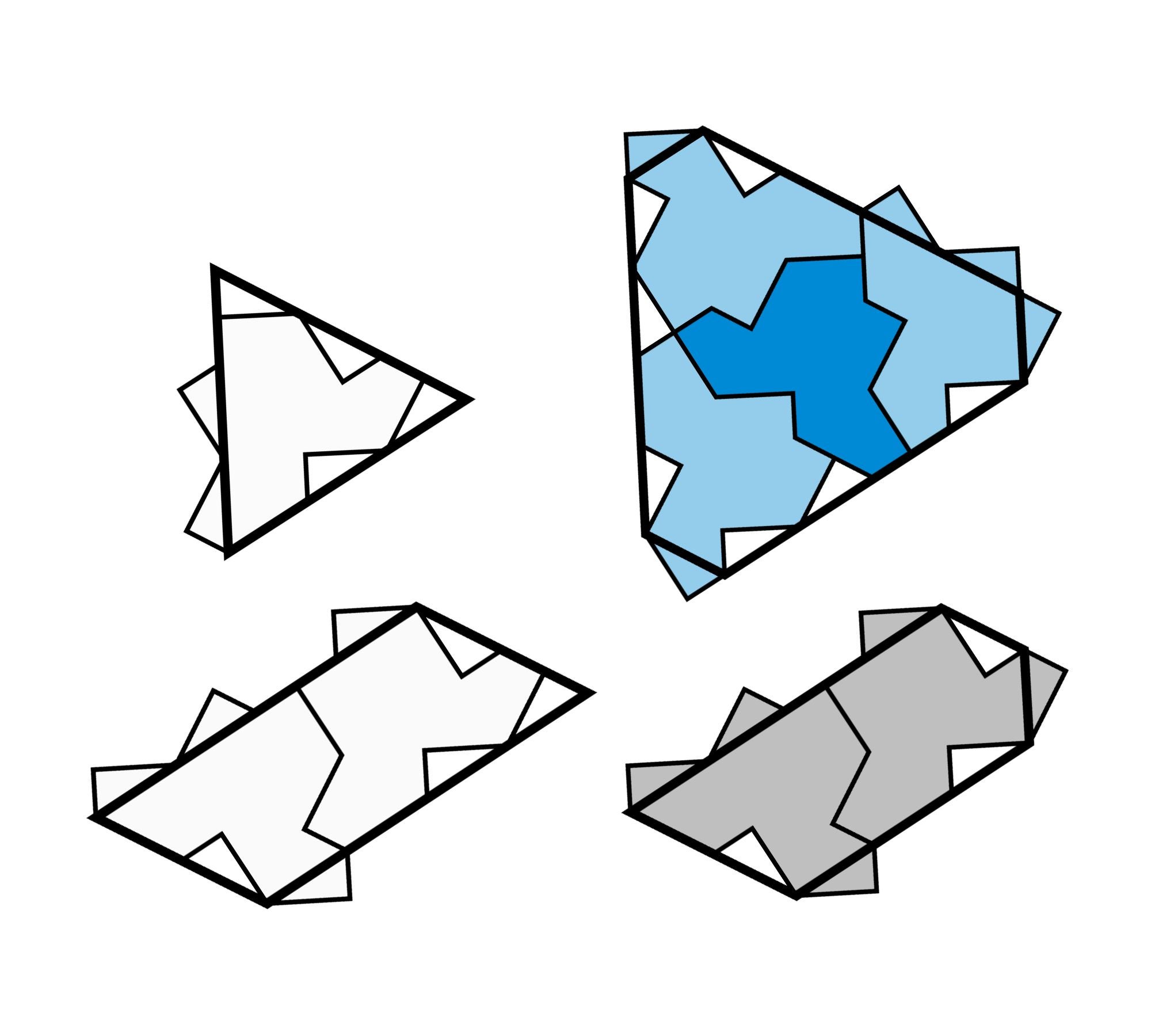

Kaplan, Goodman-Strauss, and Myers were able to show something similar for the hat-shaped Einstein tile proposed by Smith. To make the tiles easier to work with, I smoothed the jagged edges of the hat into a more recognizable and convenient shape. For example, a single hat tile can be approximated by a triangle. I also used clusters of multiple Einstein tiles to create different shapes. They were able to arrange four hat tiles in a hexagonal structure, two tiles in a pentagon, and another combination of two tiles in a parallelogram. These four smooth shapes, each composed entirely of Einstein tiles, allowed the pattern to completely cover the plane.

Mathematicians proved that this tile contained no repeating patterns, as these four special shapes formed a hierarchical structure, similar to Robinson’s set of six tiles. Putting these four Einstein tile clusters (hexagons, pentagons, parallelograms, and triangles) together inevitably creates one large version of him of the same shape. These larger shapes are then combined to create even larger versions of those shapes. This process can be repeated indefinitely, resulting in a hierarchical structure. Therefore, the entire pattern cannot be divided into repeating sections. Simply sliding one part of the pattern to another place breaks that overarching structure.

%5B2%5D_webp.jpeg)

Two proofs are better than one

The proof required complex calculations, so the three scientists enlisted the help of computers. They released their computer-assisted proofs freely so that anyone could check them for errors.

But Myers was still not satisfied. He creates a new method of proving aperiodicity that can be done manually without the use of a computer by showing that Einstein’s hat is connected to other well-known tilings that are easy to study. Did. These related tiles consist of shapes called polydiamonds, which are simple tiles formed by combining equilateral triangles. Myers adjusted part of the rim of Einstein’s hat to form two different polydiamond arrangements of his that follow the same tiling his pattern as the hat. Despite the visual differences, all three of these he placements have the same characteristics. If the mathematician can prove that his tiling of both polydiamonds is aperiodic, then the original tiling must also be aperiodic.

Thankfully, for polydiamonds, the proof is a basic math problem. Mathematicians can express the symmetry of a polydiamond arrangement in a quantity called a translation vector. If the two new placements contain repeating patterns, their translation vector lengths must be related to each other. Specifically, their ratio must be a rational number. But instead, the vectors had ratios of square roots of 2 (arguably irrational numbers). This indicates that the arrangement of polydiamonds is not periodic. So the original hat tile was indeed Einstein.

Myers’ new proof method could also be useful for other tilings, the scientists explain in their paper. But for now, veterans and amateurs alike are thrilled to get their hands on the long-awaited Einstein his tile. The possibilities for home decoration are literally endless.As Williams College mathematician Colin Adams put it, new scientist“If I was tiling now, I would put it in the bathroom.”

This article originally appeared on science spectrum Reproduced with permission.