About 30 years ago, in the remote Arctic Circle, a group of Inuit middle school students and their teachers invented the first new number system in the Western Hemisphere in over a century. Named after the Alaskan village in which they were created, “Kaktovic numbers” looked quite different from decimal numbers and functioned differently. It was particularly well-suited for quick, visual calculations and quickly spread throughout the region. Now, with the support of Silicon Valley, it is readily available on smartphones and computers, providing a bridge for kaktobic numbers to cross into the digital realm.

Today’s world of numbers is dominated by the Hindu-Arabic decimal system. Adopted by almost all societies, this system is what many think of as “numbers”, values represented in written form using the digits 0 through 9.

The Alaskan Inuit language, known as Iupiak, uses a verbal counting system built around the human body. Quantities are first described in groups of 5, 10, 15 and then in sets of 20. The system is “really the number of hands and the number of toes,” says Nuluqutaaq Maggie Pollock. Utkiagvik, a city 300 miles northwest of where numbers were invented. For example, she said: stable— the Inupiaq word for five — comes from the word for arm. Tarik“In one arm of yours, stable fingers,” explains Pollock. Inuignac, 20 words represent the whole person. In traditional practice, the body also functions as a mathematical multi-tool. “When my mother made me a parka, she would use her thumb and middle finger to gauge how many cuts I could make in her material,” Pollock says. “Before rulers and rulers, [Iñupiat people] I used my hands and fingers to calculate and measure. “

During the 19th and 20th centuries, American schools suppressed the Iñupiaq language, first violently and then quietly. “We had a village tutor who helped us integrate into the white world,” Pollock says of her own education. It was torture for them.” By the 1990s, the Inupiaq counting system was dangerously close to oblivion.

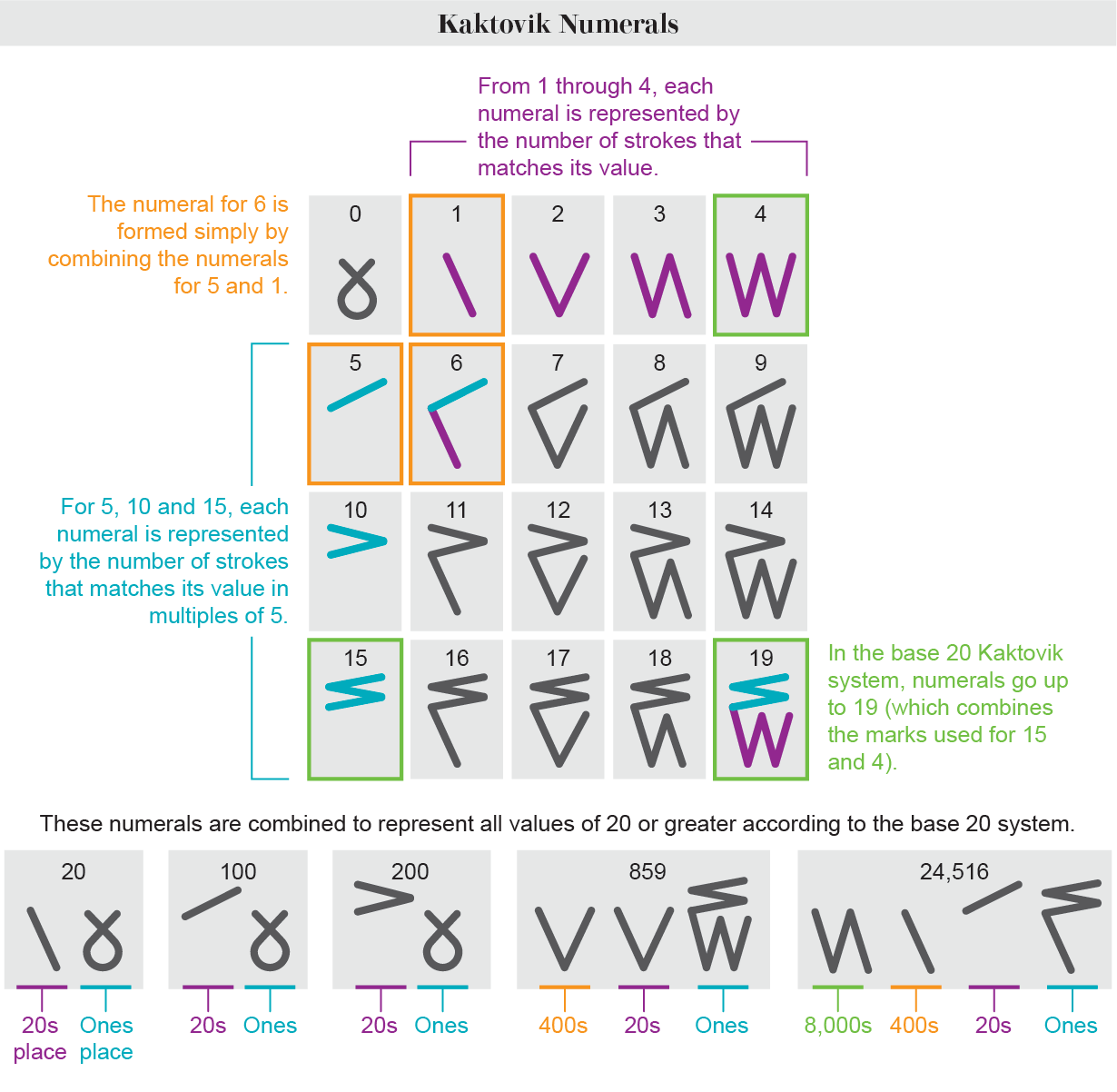

Kaktovik Numbers started as a class project to adapt counting to letters. Numbers based on tally symbols “similar” to the Inupiaq words they represent. For example, the Inupiaq “” for 18Akimiac Five,” It means “15-3” and is drawn with 3 horizontal lines representing 3 groups of 5 (15) above 3 vertical lines representing 3’s.

“Inupiaq didn’t have a word for 0,” says William Clark Bartley, a teacher who helped develop numbers. “The girl who gave us the 0 symbol had her arms crossed over her head as if nothing was there.” Adding to the unique set of numbers, she invented what mathematicians call her base-20 position value system. (Technically, this is a two-dimensional position value system with 20 primary bases and 5 subbases.)

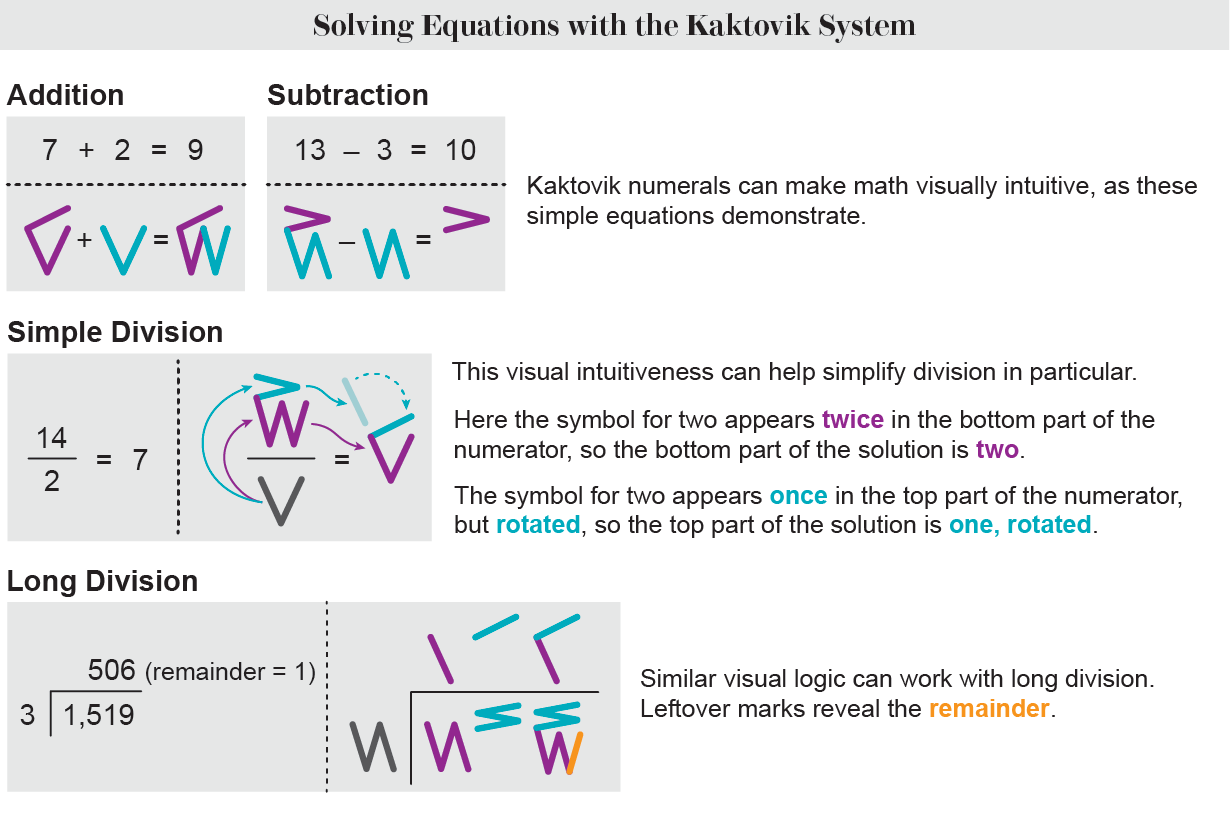

Arithmetic operations with cactobic numbers are highly visual due to their aggregation-inspired design. Addition, subtraction, and even long division become almost geometric. Hindu-Arabic numerals are a cumbersome system, but “students have found that they can solve their problems better and faster with numbers,” he says.

“Inupiak’s way of knowing is often by showing,” adds Kajina Tena Judkins, director of Iupiak education in the North Slope Borough of northern Alaska. Visualizing the arithmetic makes these concepts much easier to understand, she says.

At first, students converted their assigned math problems into Kaktovic numbers to do their calculations, but in a Kaktovic middle school math class, in 1997, they did the same as their Hindu-Arabic counterparts. I started teaching numbers. In both systems, standardized mathematics test scores jumped from below the 20th percentile to “well above” the national average. Meanwhile, the school board of her Utqiagvik, the county seat of the North Slope Borough, has passed a resolution disseminating figures along the Arctic coast for about 500 miles. The system was also endorsed by the Inuit Circumpolar Council, which represents his 180,000 Inuit across Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Russia.

However, from 2002 to 2015, under the federal No Child Left Behind Act, schools faced severe sanctions or even closures for not meeting state standards. Proven educational effect of the system. “Today is the only place [they’re] It’s actually an Inupiak language classroom,” says Chrisan Justice, a specialist in the North Slope Borough’s Inupiak Education Department. “We’re just blowing coal.”

Now, with backing from Silicon Valley, Kakutovic’s numbers are reigniting. The numbers were included in his September 2022 Unicode update, thanks to the efforts of linguists working with his Encoding Initiative at the University of California, Berkeley. Unicode is an international information technology standard that enables the digitization of the world’s written languages. The new release, Unicode 15.0, provides virtual identifiers for each cactobic digit so developers can incorporate them into digital displays. “It’s really revolutionary for us,” says Judkins. “Now I have to use pictures of numbers or write them by hand.”

There is still work to be done. Google is creating fonts for numbers based on the Unicode update, says Craig Cornelius, his software engineer at Google who works on the digital preservation of endangered languages. The company said he did a “pre-release” of the font in March that you can download to your computer, but you won’t see it on the Android operating system until at least the end of the summer. Desktop and mobile keyboards with numbers should also be manufactured.

But there is growing excitement about the cyber debut of traditional systems. “If you go to the author of a math textbook and say, ‘Hey, can you convert the Arabic numbers into kaktobic numbers and make a textbook for them?’ Judkins says.

The inclusion of Unicode also pushes the boundaries of what is mathematically possible with Kaktovik numbers. At higher levels, mathematics becomes an increasingly digital field. Basic theory can be drawn on a blackboard, but complex problems often need to be solved on a computer. Without digital availability, kaktovic numbers would be confined to the arithmetic wheelhouse, as Inupiaq is being revived for widespread use in modern times. Being able to input cactus numbers into computational engines such as WolframAlpha will be a “game changer. You will almost have a choice: am I going to speak in English or am I going to speak in Inupiac?” If I’m in Inupiaq, I’m all using Kaktovic numbers.”

About 3,000 miles away in Oklahoma, Unicode has similar potential for the Cherokee community. In the early 1800s, Cherokee mathematician Sequoia invented syllables for the Cherokee alphabet. “At the same time, he also developed a numbering system,” says Roy Bonney, Cherokee Nation’s Language Program Manager. Cherokee numerals were not approved by the tribal government until 2012. A long history of trading with French and English settlers meant that Hindu-Arabic numerals were already in use when Cherokee numerals were invented.

It’s unclear if the Cherokee digits became popular after that, but Boney reports that interest in the system is growing. “We have numbers and we have to use them,” he says. “Although we’ve been slow, we’ve been introducing numbers into the educational environment,” and we’re starting to demonstrate the community use necessary to incorporate them into Unicode. Once numbers are involved, Boney and his colleagues hope to create a programming language using Cherokee, his scripts and numbers.

The ubiquity of Hindu-Arabic numerals is powerful and often comes at the expense of culturally meaningful systems. Today, however, these systems are slowly digitizing, creating opportunities for use that were unthinkable two years ago. As Nuluqutaaq Maggie Pollock says, “This is just the beginning.”