A mysterious bundle of encrypted letters hidden in the French National Library (BnF) has turned out to be a never-before-seen letter from Mary, Queen of Scots.

Also known as Mary Stuart, then deposed Queen of Scotland and contender for the English throne, wrote these 57 coded letters between 1578 and 1584. rice field. Most of these letters were addressed to the French Ambassador to Great Britain, Michel de Castelnaud. At the time, Mary was in the custody of the Earl of Shrewsbury, and she was imprisoned because Queen Elizabeth feared Mary and her supporters intended to appoint her as Queen of England. A later letter, not part of this cache, written in 1586, ultimately spells out Mary’s fate: one of Elizabeth’s spies, Lord Francis Her Walsingham, tricked Mary into deceiving her to believe that the letter was safe, and intercepted a letter supporting Elizabeth’s assassination. As a result, Mary was beheaded for treason in 1587.

While combing through the BnF archives, cryptographer George Lasry and other scientists of the DECRYPT project, a multi-university project that seeks to find and decipher historic ciphers, discovered Italian ciphers dating back to the early 1500s. I came across a page of ciphers intermingled with documents. Encrypted letters were believed to be Italian. But when researchers began trying to crack the code, they realized that the words had to be in French to make sense.

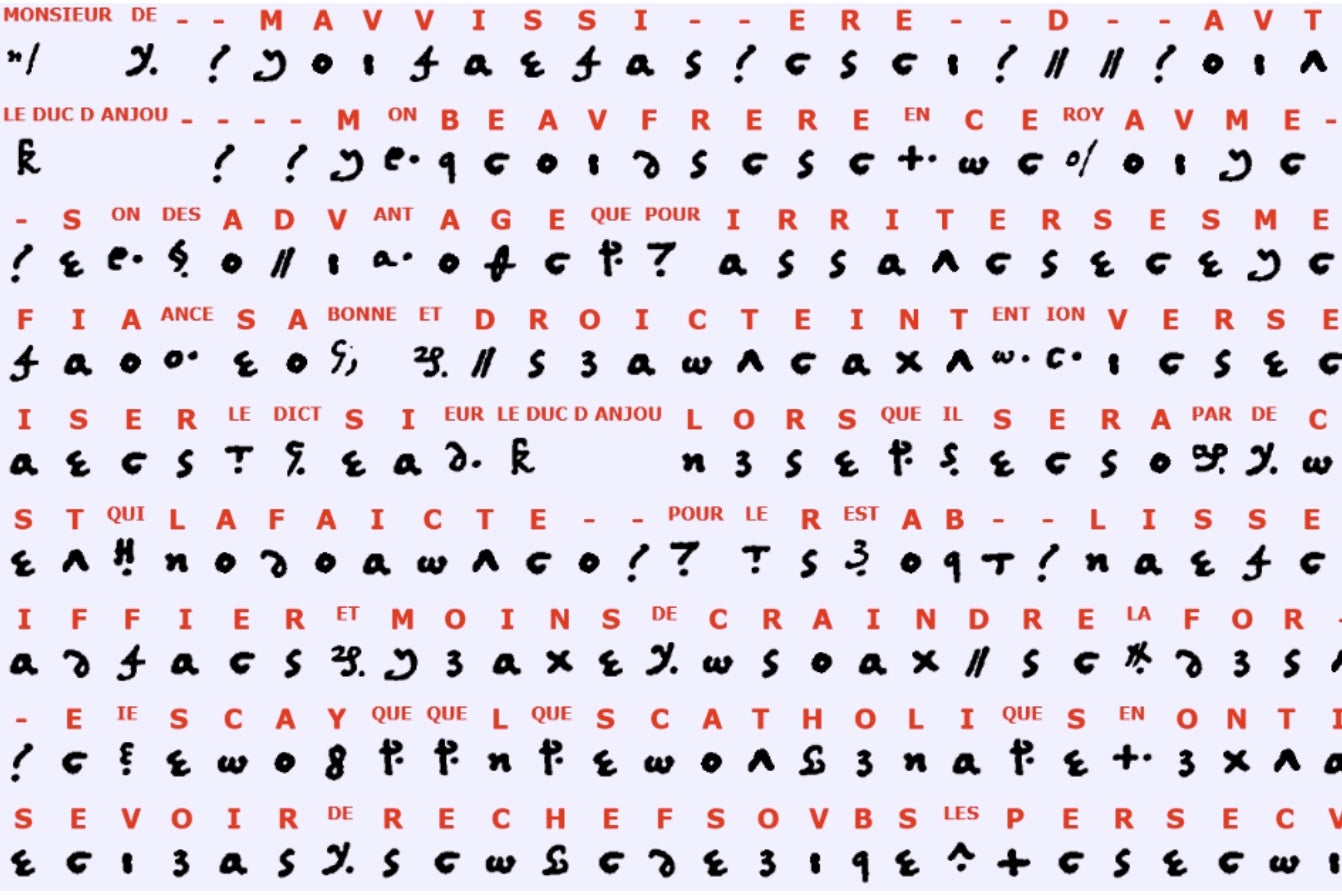

The letter used what is known as homophonic encryption, researchers explain in a study published Tuesday in the journal cryptographyIn such ciphers, each letter of the alphabet is replaced with a specific symbol. However, since certain characters such as ‘e’ occur much more frequently than others, simple substitution ciphers are easy to crack. That’s why homophonic ciphers used multiple symbols interchangeably for high-frequency letters, he says, Lasry. To make things even more complicated, Mary’s cipher, like other ciphers of this type, used specialized symbols to replace frequent words and common word segments.

“Working on deciphering was like working on an onion that needed to be peeled,” says Lasry. “The cipher is very complicated and we worked on it step by step.”

Little by little, the truth of the letter was revealed. First I noticed that the letter was not in Italian. Later, French phrases such as “” were discovered.my freedom”, suggesting that the writer wanted freedom. Finally, the obvious name popped up: Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth’s notorious spymaster.

Most of the 57 letters had never been seen until Lasry and his colleagues discovered them. However, his seven of them were intercepted and decrypted by his Walsingham network, so the decrypted copies were kept in the National Archives of England. These matching copies helped confirm beyond doubt that Mary was a writer, says Lasry. Attempting to get the French ambassador to make demands on Elizabeth on her behalf, raising her suspicions that the ongoing negotiations over her freedom may not be in good faith. And, Lasry says, he felt little of Mary’s personal feelings. Susan Dolan, a historian at the University of Oxford, who is working on a project on Mary but is not involved in her new research, said her diplomatic focus was exciting to historians. I’m here. Much of the content of the letters, Doran says, was about wider diplomatic issues than just Mary’s attempts to regain the Scottish throne or the struggle for the English throne.

“She is in negotiations with the Spaniards, with the French – as is evident from these letters – with Scotland and Elizabeth. “It really deepens the sense of the plot,” says Doran. “There’s so much more to Mary than plot.”

Historians will now need to peruse the letters and place them in the context of Mary’s life and circumstances, says Lasry. Well, there are new words from Mary, Queen of Scots. “We’ve only scratched the surface,” he says, Lasry.