University of Illinois Archives

Brilliant graphics, touchscreens, speech synthesizers, messaging apps, games, educational software, and more are not your child’s iPad. It’s the mid-1970s and you’re using a PLATO.

A far cry from its relatively primitive contemporaries of teletypes and punch cards, PLATO was something else altogether. If you were lucky enough to be near the University of Illinois at Urbana, his University of Champaign (UIUC) about half a century ago, you might have had a chance to build your future. Many of the computing innovations we take for granted began with this system, and even today some of PLATO’s capabilities have never been replicated exactly. Today we take a look back at this influential tech testbed and see how you can experience it now.

from the space race space war

Don Bitzer received his Ph.D. in electrical engineering from UIUC in 1959, but his eyes were on something bigger than circuits. “I had read the prediction that 50% of our high school graduates would be functionally illiterate,” he later told his Wired interviewer. “We had a physicist, Chalmers Sherwin, who was not afraid to ask big questions. Can’t you use it?”

The system should be, in Sherwin’s words, “a book with feedback.”

The question was timely. Higher education was coping with a massive influx of students, and science and technology quickly became a national priority as the Soviets clearly won the space race with his 1957 Sputnik launch. The devised “automatic education” attracted interest from both academia and the military. Sherwin said he went to William Everett, the dean of the engineering department, and he asked Daniel Alpert, the physicist, director of the Control Systems Laboratory, to bring together a group of engineers, educators, mathematicians and psychologists to recommended to investigate. However, the group encountered a serious obstacle in that members who could teach could not understand the potential skills needed and vice versa.

Alpert, exhausted after weeks of fruitless discussions, was about to terminate the committee, but it wasn’t until he had a ramshackle argument with Bitzer that Bitzer was already “part of the interface for teaching with computers.” Using a grant from the U.S. Army Signal Corps, Alpert gave him two weeks, and Bitzer set to work.

For the actual processing, Bitzer used the university’s existing ILLIAC I (then simply “ILLIAC”) computer. It was the first computer entirely built and owned by an educational institution, a clone of his ORDVAC some time ago. Both he was manufactured in 1952 and had full software compatibility. IILIAC’s 2,718 tubes gave it more computing power than Bell Labs had in 1956, with an additional time of 75 microseconds and an average multiplication time of 700 microseconds, 1024 40-bit memory words, and 10,240 words. was equipped with a magnetic drum unit. Bitzer designed the software in collaboration with programmer Peter Braunfeld.

The Wide World of Computer-Based Education (Bitzer, 1976)

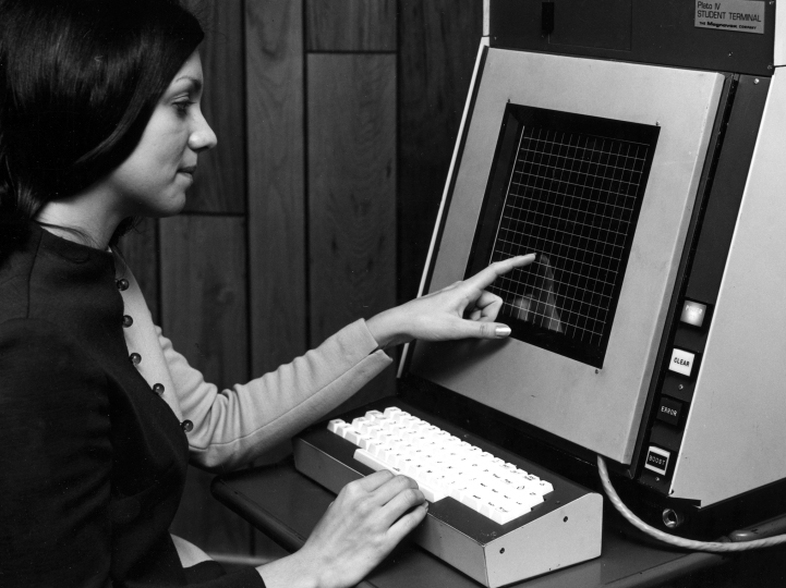

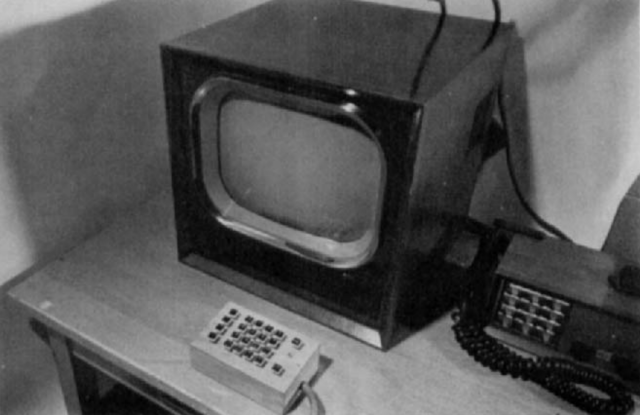

The front end was a civilian television set with a self-maintaining storage tube display and attached small keypad originally used in naval tactical defense systems. The on-screen slides were displayed from a projector under ILLIAC control and manipulated by control keys. ILLIAC was able to overlay vector graphics and text onto slides at 45 characters per second via what Bitzer and Braunfeld called an “electronic blackboard.” This system provided interactive feedback when most computer operations were batched. This computer he named PLATO in 1960 and was later given the backro name as “Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations”. Even though he could only have one user running the lesson at a time, the prototype worked.

U.S. Office of Naval Research Digital Computer Newsletter, October 1961-April 1962

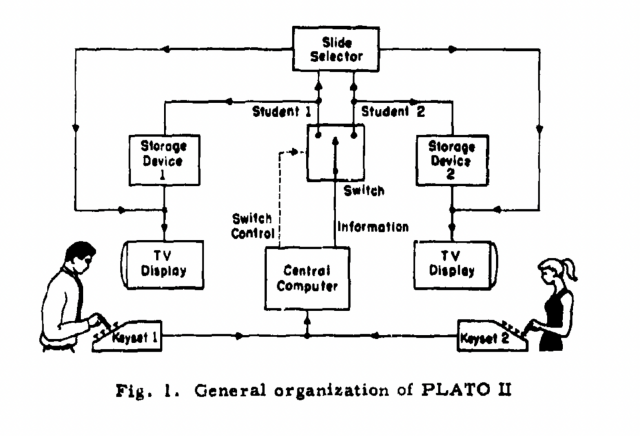

The concept spread rapidly. In 1961 he came out with the PLATO II, which offered a full alphanumeric keyboard plus special keys based on the PLATO I. These keys include CONTINUE (next slide), REVERSE (previous), JUDGE (to check if an answer is correct), ERASE, HELP (to provide supplemental material or to clarify an answer), and when students “suddenly I realized the answer to the main sequence problem, and decided to answer it immediately.

But its biggest innovation is time-sharing, allowing multiple students to use the system simultaneously for the first time. I had to carefully program the user’s slice of time so that no keystrokes were lost in each session. Unfortunately, ILLIAC’s memory capacity stymied this progress, limiting system capacity to her two users at a time and limiting interactivity by limiting “secondary help sequences.”